Vertical Divider

Musing on Technology

Smartphone Cameras Address the Issues of Auto-Focus,

Cost, Focal Length in Very Small Spaces

June 07, 2020

In modern lenses, there’s usually a autofocus mechanism of some kind. Nikon used a motor in the camera body for a while, but most camera systems employ some kind of in-lens motor. SLR use simply ways to offer mechanical drive to a classic focusing helical. In mirrorless cameras, it’s typical to “focus by wire,” in that the focus knob is just a position sensor, and the motor is employed in the lens for both automatic and manual focusing. This has led to other sorts of autofocusing mechanisms, such as linear voice-coil motors, as shown here. Coupled with computer design, lens focus can be made better and faster by independent motors on different lens groups with in a lens.

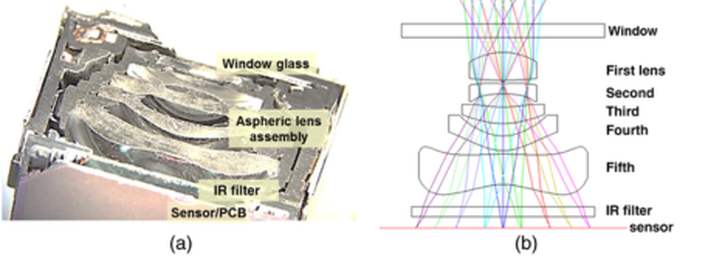

A smartphone lens introduces a few additional complexities. First, smartphone lens are all under $5.00 cost to the manufacturer, and more typically around $2-$3. They’re pretty much always made of injection-molded optical plastic, which allows for huge mass production, helping to lower this cost. The following is a cutaway (a) and diagram (b) of a five element smartphone lens The window is a protective pane made of hard glass or sometimes sapphire.

Figure 1: Cutaway & Five Element Smartphone Lens

Smartphone Cameras Address the Issues of Auto-Focus,

Cost, Focal Length in Very Small Spaces

June 07, 2020

In modern lenses, there’s usually a autofocus mechanism of some kind. Nikon used a motor in the camera body for a while, but most camera systems employ some kind of in-lens motor. SLR use simply ways to offer mechanical drive to a classic focusing helical. In mirrorless cameras, it’s typical to “focus by wire,” in that the focus knob is just a position sensor, and the motor is employed in the lens for both automatic and manual focusing. This has led to other sorts of autofocusing mechanisms, such as linear voice-coil motors, as shown here. Coupled with computer design, lens focus can be made better and faster by independent motors on different lens groups with in a lens.

A smartphone lens introduces a few additional complexities. First, smartphone lens are all under $5.00 cost to the manufacturer, and more typically around $2-$3. They’re pretty much always made of injection-molded optical plastic, which allows for huge mass production, helping to lower this cost. The following is a cutaway (a) and diagram (b) of a five element smartphone lens The window is a protective pane made of hard glass or sometimes sapphire.

Figure 1: Cutaway & Five Element Smartphone Lens

Source: Quora

It not only protects the very soft plastic elements, but it keeps dust out of systems with image stabilization. In most stabilized phone lenses, rather than move an optical element or the sensor, the entire lens/camera assembly moves. Thus, it’s got to be free within the camera module, allowing the possibility of dust accumulation if not sealed in front.

Figure 2: iPhone lens breakaway

Figure 2: iPhone lens breakaway

Source: DXOMark Lab

The advantages of using an injection molded optical plastic lens is the ability to mold the lens and the “barrel” together, so the elements basically just stack together, no need for additional precision alignment. Since it’s molded, lens elements can be asymmetrical. And, plastic is light compared to glass. But plastic is inferior in many ways to glass. It has relatively low structural stability, and can deform when the phone is moving, or when subject to resonant sounds. It can absorb moisture, changing the lensing just a bit, though today’s water resistant phones somewhat protect absorption. It has poor thermal stability versus glass and the phone size puts a hard limit on both lens focal length and the number of possible elements. As shown, most phone lenses are 5–6 elements, maximum, and the focal length is rarely longer than 6mm.

Figure 3: Elements of Phone Lens

Source: DXOMark Lab

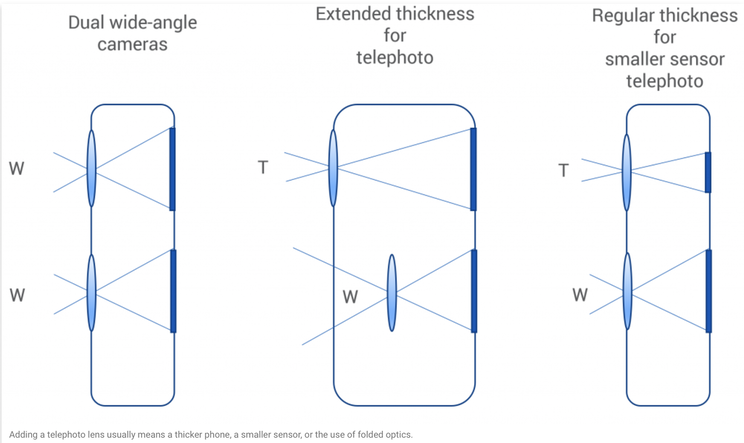

Even at 6mm, if the phone makers wants a “portrait” lens, maybe even a telescopic/telephoto camera, it may cause the camera body to be thicker or the image sensor smaller. For example, the iPhone 11 Pro has 12 megapixel sensors for all three cameras. However, the portrait camera uses a 6mm f/2.0 lens with a 1/3.4″ sensor, versus the main wide-angle camera, which uses a 4.25mm f/1.8 lens with a larger 1/2.55″ sensor. It’s the need to keep the phone thin that determines the size of the smartphone lens versus a dedicated camera, which is why multiple cameras are used, whereas even a cheap point-and-shoot camera employs a zoom (aka, variable focal length) lens.

Figure 4: Point & Shoot Camera

Source: Quora

A zoom lens is inherently more complex, with more elements. While the term “zoom” is used incorrectly in the context of modern smartphone cameras, the only actual zoom is a software trick to switch between cameras and, in-between, interpolate in software between multiple cameras. The only optical zooms found in phones have been in hybrid phone/cameras, like this Samsung Galaxy Zoom K. The thicker nature of this phone pretty much made it flop in the market. We demand good pocket computers out of our phones, the cameras are nearly always a secondary concern.

Smartphone cameras struggle with wide and particularly ultrawide lenses. Unless the lens is a “fisheye” lens, it is expected to be “rectilinear” — straight lines remain straight. Since a smartphone nearly always does image processing, some of the formula for camera success is based on digital corrections of lens flaws. On Samsung’s ultrawide cameras, the correction can be switch on or off. Some modern electronic lenses, such as those for Micro Four Thirds, can include lens characterization data that allows for similar corrections, though not likely as severe. But as with the smartphones, low cost, ultra-compact consumer lenses still deliver acceptable results to the user. These can include rectilinear distortions, chromatic aberrations, and other lens imperfections.

Figure 5: Fisheye Lens

Source: Quora

Another issue is aperture. There is currently only one camera series on the market in phones that have variable aperture: Samsung’s f/1.5 lens, used in the 2018 and 2019 Galaxy S and Note. It is the fastest lens on any smartphone at f/1.5, and it’s second aperture setting is f/2.4. More apertures are limited by diffraction. When light passes through an aperture, it bends — the smaller the aperture, the more bending, which means that a perfect point of light focuses as a disc, dubbed the Airy Disc (George Airy developed the mathematics of diffraction). If the Airy Disc gets much larger than the sensor’s pixel size, it looks out-of-focus and the image gets fuzzier. This year’s crop of 48 and 64 megapixel phone cameras don’t have lenses fast enough to actually resolve 48 or 64 megapixels, regardless of how perfectly made the lens is otherwise. These chips all have 800nm pixel grids. But for Samsung’s 12 megapixel sensor, f/2.4 is probably right on the edge of diffraction. At f/2.4, the image actually gets a bit sharper, although some reviewers see a bit of difference at f/2.4, a bit software images at f/1.5. Others didn’t see the difference. And Samsung’s default image finishing agent uses a bit too much digital sharpening of the image, which does seem to make the Samsung sharper than other 12 megapixel phones, but maybe not in a good way? Certainly, smartphone lenses are designed with the idea they’ll only ever be used at full aperture, just like cheap P&S and Instamatic cameras going back decades. That does not, however, guarantee that they are necessarily at peak sharpness wide open. The 48 megapixel phone will be a little fuzzy at full aperture for a 48 megapixel camera, and it would get worse with each smaller aperture. Low-end point-and-shoot cameras also don’t have aperture settings, thanks to the same diffraction problems.

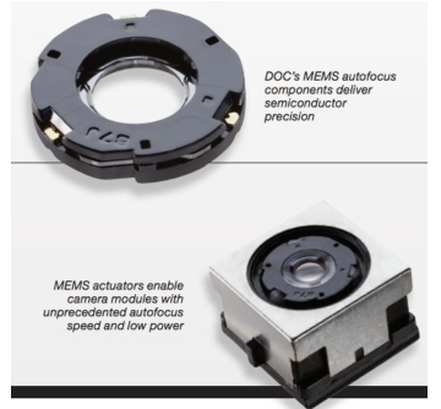

Figure 6: MEMS Auto Focus

Source: Quora

Phones have used various means to focus the lens, but it’s always electronic. There are no phones with a focus knob. Some phones have used linear voice coil motors for AF, but the hot new thing is MEMS (Micro Electro-Mechanical System) focusing units. MEMS AF tends to be faster than LVCM, at least in phones.

Figure 7: MEMS Auto Focus Unit

Source: Quora

Some phones also manage autofocusing via laser rangefinders. These simply provide information to the AF system, but the cameras generally have their own alternate focusing means. Early smartphones didn’t have any focusing means. With smaller sensors, narrower apertures, and in particular, no user demand for phones to be used as a replacement for a consumer point-and-shoot camera, this went on unchallenged for a few years. When phones did get autofocus, it wasn’t for amateur photography, but rather, for increasing the utility of the camera. It could be used to focus on barcodes or scan checks for deposits. It was really only after the faster, autofocusing cameras, around 2010–2011, that the phone-as-camera really started taking off. Ultrawide angle lenses is the latest thing in phones, sometimes have fixed focus again. That’s because at 1.5–2.0mm in focal length and usually around an f/2.4 aperture, these lenses have a hyperfocal range from maybe 1–2″ to infinity. From: Quora

|

Contact Us

|

Barry Young

|