Vertical Divider

Musing on Competitive Technology

LEDs and the Excessive Use of Blue

February 23, 2020

The first official LED was created in 1927 by Russian inventor Oleg Losev, however, the discovery of electroluminescence was made two decades prior. British experimenter H. J. Round of Marconi Labs was the first to report the phenomenon in 1907. He found that silicon carbide would glow with a yellowish light when a potential of ten volts was applied to it. This set off years of experimenting with materials such as silicon carbide, gallium arsenide, gallium antimonide, indium phosphide, and silicon-germanium in an attempt to create a practical device. In 1955, Rubin Braunstein reported infrared emission from gallium arsenide, however James R. Biard and Gary Pittman of Texas Instruments presented the first IR lamp (PDF) in 1961 which was the first practical LED to be patented in the August of the same year. Consequently, the first commercial LED was an IR LED with 890 nm light output and was called the SNX-100. The era of the visible LED began in 1962 by Nick Holonyak, Jr. who was working at General Electric at the time. He discovered the red LED and published the results in the Applied Physics Letters on December 1, 1962 and currently holds around 41 patents to his name. He is known as the father of the visible LED and is also responsible for the laser diode commonly used in CD and DVD players. A decade later came the discovery of the yellow LED, M. George Craford, who happens to be a former graduate student of Holonyak. In 2014, three scientists, Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano, and Shuji Nakamura won the Nobel prize for inventing the blue LED in the early 1990s. Blue LEDs, quickly fell into overuse: the technology rapidly became the sigil of all that was new and great, much to the ocular pain of the buying public. A status LED, most would agree, is there to indicate status. It need only deliver enough light to be seen when observed by a querying eye. What it need not do is glow with the intensity of a dying star, or illuminate an entire room for that matter. But, in the desperate attempts of product designers to appear on the cutting edge, the new, brighter LED triumphed over all in these applications. The pain this causes to the user is manifold. The number of electronic devices in the home has proliferated in past decades, the vast majority of which each have their own status LED. Worse, many of these are used in the bedroom, be it laptops, phone chargers, televisions, or others. With the increased brightness of these indicators, many of which are on all the time, the average sleeping space is lit like a Christmas tree.

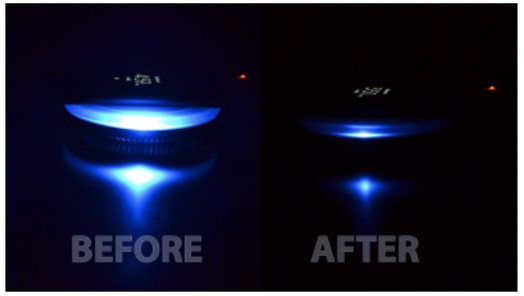

Figure 1: Samsung Charger So Bright That Users Hacked It To Be Dimmer.

LEDs and the Excessive Use of Blue

February 23, 2020

The first official LED was created in 1927 by Russian inventor Oleg Losev, however, the discovery of electroluminescence was made two decades prior. British experimenter H. J. Round of Marconi Labs was the first to report the phenomenon in 1907. He found that silicon carbide would glow with a yellowish light when a potential of ten volts was applied to it. This set off years of experimenting with materials such as silicon carbide, gallium arsenide, gallium antimonide, indium phosphide, and silicon-germanium in an attempt to create a practical device. In 1955, Rubin Braunstein reported infrared emission from gallium arsenide, however James R. Biard and Gary Pittman of Texas Instruments presented the first IR lamp (PDF) in 1961 which was the first practical LED to be patented in the August of the same year. Consequently, the first commercial LED was an IR LED with 890 nm light output and was called the SNX-100. The era of the visible LED began in 1962 by Nick Holonyak, Jr. who was working at General Electric at the time. He discovered the red LED and published the results in the Applied Physics Letters on December 1, 1962 and currently holds around 41 patents to his name. He is known as the father of the visible LED and is also responsible for the laser diode commonly used in CD and DVD players. A decade later came the discovery of the yellow LED, M. George Craford, who happens to be a former graduate student of Holonyak. In 2014, three scientists, Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano, and Shuji Nakamura won the Nobel prize for inventing the blue LED in the early 1990s. Blue LEDs, quickly fell into overuse: the technology rapidly became the sigil of all that was new and great, much to the ocular pain of the buying public. A status LED, most would agree, is there to indicate status. It need only deliver enough light to be seen when observed by a querying eye. What it need not do is glow with the intensity of a dying star, or illuminate an entire room for that matter. But, in the desperate attempts of product designers to appear on the cutting edge, the new, brighter LED triumphed over all in these applications. The pain this causes to the user is manifold. The number of electronic devices in the home has proliferated in past decades, the vast majority of which each have their own status LED. Worse, many of these are used in the bedroom, be it laptops, phone chargers, televisions, or others. With the increased brightness of these indicators, many of which are on all the time, the average sleeping space is lit like a Christmas tree.

Figure 1: Samsung Charger So Bright That Users Hacked It To Be Dimmer.

Source: VIPvog, YouTube

The fad of using blue LEDs for power indicators only makes this problem worse. The human eye features special receptors sensitive to blue light that are not only used for vision. These cells are also used to detect the blue light from the sky, coordinating our internal Circadian rhythms to the Earth’s day/night cycle. Exposure to artificial blue light can interfere with this system, with research suggesting it may have a negative effect on sleep cycles. Part of the problem is that the majority of LEDs on the market now are efficient, high brightness designs and get included in designs with little regard for their excessive light output simply because it’s easy to do so, or maybe the designers have just failed to update their standard resistor value. A bright glow can be seen on the ceiling because the Caps Lock was left on before retiring for bed. The same goes for phone chargers and laptop chargers too. Devices shouldn’t have to be wrapped in several layers of electrical tape to hide a light that should be little more than a dim glow to begin with. If the device is reliable enough, it shouldn’t need to be looked at anyway! Clearly, good status LEDs serve a purpose. They tell us that we’re composing a highly aggressive email with the scary big letters, that our charger is indeed receiving delicious AC current, or that our monitor is receiving power but isn’t really, properly turned on (okay seriously, who cares?). Crucial as they are, there’s no excuse for getting them so badly wrong. It’s important to lay out a few rules to guide their proper implementation and use.

Figure 2: The Amiga 500, With Maximum Brightness Interfering With The Human

Source: Hackaday

Excessive brightness should be avoided. As small LEDs can be easily dimmed with a simple resistor value change, there is no excuse for power or standby LEDs that light up a room. Instead, the level should be suited to typical use cases. 1980s home computers had no problems with excessively bright indicators; thus, it is suggested that readings be taken from a sample of standard Amiga 500 power LEDs. The average value found should be the upper limit for power indicators on indoor electronic devices. Power LEDs shouldn’t be looked at that often anyway, unless the hardware is highly unreliable, which is a totally different problem.

Figure 3: Power Indicators w/Too Much Brightness

Source: Hackaday

Colors should also be standardized, or at the very least, chosen with some kind of thought as to effective visual communication. Power LEDs should universally be green. None of this “blue for on” nonsense – it’s just showing off. It wasn’t cool in 2001, and it isn’t cool now. The purpose of status LEDs should also be questioned. Too many LEDs, or too many colors, can be confusing. A laptop battery charge LED should be a single color, to indicate charging – ideally green. If it’s orange and green, what does that mean, exactly? Charging, and fully charged? Fault, and charging? If a user has to look up a manual to determine the meaning of a status LED, there’s a better solution. Flashing should only be used where absolutely necessary. LEDs for hard drive and network activity should flash, as they indicate a constantly changing state. Mute LEDs on a mixing board should flash, because they’ll save noob techs when they can’t figure out why no sound is coming out. On the other hand, a standby LED on a television should never flash, because if the TV is off, it’s because nobody wants to pay attention to it.

Hopefully, these rules serve as a starting point for hardware designers in future. No longer will a charging pad, designed for a bedside table, bathe an entire room in an eerie blue glow. A TV will not blink incessantly, keeping houseguests awake as they try to sleep on the couch. With a few changes, we may all rest soundly, free from glaring visual distractions as we go about our daily lives. Of course, this is just the opinion of one grizzled engineer.

|

Contact Us

|

Barry Young

|