Vertical Divider

|

Jonathan Cooper, Patent Attorney, Discusses Qualcomm and Apple’s Patent Infringement Suit

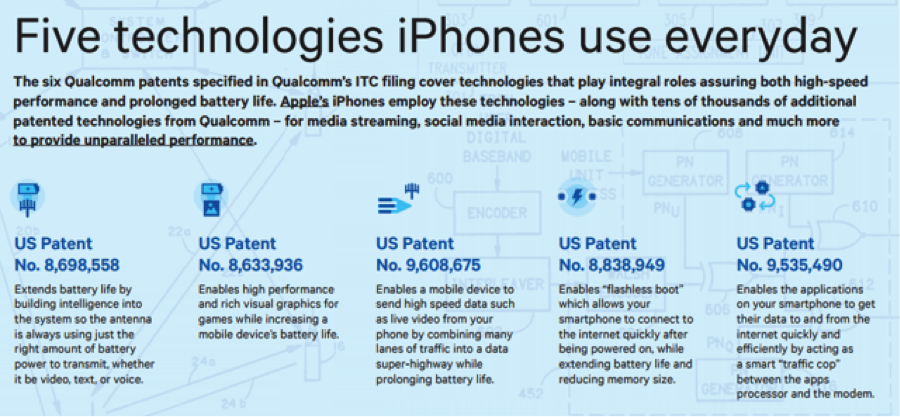

December 11, 2017 On November 29, 2017, Qualcomm filed a patent infringement suit against Apple asserting that Apple infringed five Qualcomm patents. The suit was filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California, in San Diego. Some Apple investors quickly dismissed the case, believing that Apple would easily prevail. Apple's Portrait Lighting infringes one of Qualcomm's patents, although Apple will have plausible non-infringement arguments. Apple will also likely have invalidity arguments, although their strength is difficult to determine a priori. Between that patent and its other patents, Qualcomm is likely to prevail over Apple in its patent suit. Apple is also likely to have meritorious patent claims against Qualcomm in other suits as well. Because of the strength of Qualcomm's patent portfolio, Apple will be forced to settle to prevent possible injunctions against the sale/import of iPhones. This settlement will be beneficial to Qualcomm, since the company is losing billions in revenue while this dispute continues. Qualcomm's lawsuit is related to a much larger legal and business war that is being fought between Qualcomm and Apple. The relationship between the two companies is long and complex, but ultimately boils down to a dispute over how much royalties Apple should pay Qualcomm for the use of Qualcomm's patented technologies. These patents include both standards-essential patents (SEPs) and non-SEPs. Qualcomm owns many SEPs, which claim inventions that must be used to comply with a technical standard. For example, all communications standards (Wi-Fi, cellular, and others) will be covered by a substantial number of SEPs, which are subject to Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory ["RAND"] licensing commitments.

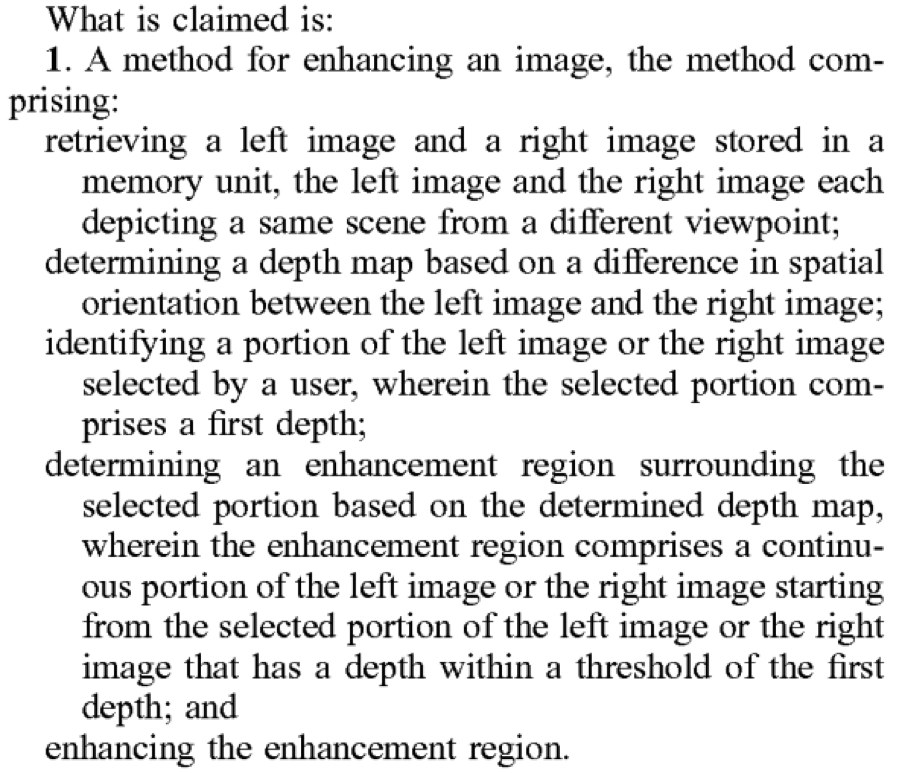

The patents at issue in this suit are not SEPs, however. Therefore, there are no RAND commitments for the patents at issue in this case. The patents at suit are U.S. Patent No. 9,154,356 (“the ’356 patent”), U.S. Patent No. 9,473,336 (“the ’336 patent”), U.S. Patent No. 8,063,674 (“the ’674 patent”), U.S. Patent 7,693,002 (“the ’002 patent”), and U.S. Patent No. 9,552,633 (“the ’633 patent”). Details of the infringement allegations for each of these patents can be found in Qualcomm's filing. In short, each of the first four patents is related to technical inventions that discuss improvements that can be made in chipsets in mobile devices. These technical inventions require analysis of chips and design documents to determine infringement. In general, the '356 patent and '336 patent are inventions related to the use of low noise amplifiers (LNAs) to aggregate carrier signals. The patents are said to improve battery life and to offer cost and performance benefits, respectively. The '674 patent is related to an improved power on/power off control (POC network), which is a part of a processor, and the improvement reduces power consumption and improves battery life. The '002 patent relates to improved designs of word line drivers, which prolong battery life. Improving battery life is a primary motivation for many mobile patents, so the focus on power consumption and battery life in these patents is not atypical. For each of these patents, both parties will conduct discovery to find as many relevant development documents as possible. Each party will make a series of document requests from the other party to build up evidence for their side. This will result in many thousands of documents being produced. Qualcomm will seek, among other things, documents that show the design process of Apple's chipsets and documents related to how those chipsets operate, to see if the infringe Qualcomm's patents. Apple will seek documents from Qualcomm's design process, which, among other things, might show previous inventions that inspired Qualcomm's engineers. This may allow Apple to show that Qualcomm's patent is invalid since it would have been obvious to a skilled person at the time the patent was filed. Unlike the other asserted patents, the '633 patent is directed to a consumer-accessible software feature of Apple devices rather than the inner workings of chips inside a device.

This method claim has five steps or elements. For Qualcomm to show infringement, they must demonstrate that Apple's devices carry out each of these five elements. The claim requires two images taken in stereo, a left image and a right image, and a determination of a depth map based on those two images. This is possible by comparing the difference in location in objects between the two images: Distant objects will be in similar positions in both images, while closer objects will be in spatially different positions in the two images. Based on these differences, the software can determine an approximate depth of the objects in the images. The claim then includes a user-selected portion of the image. A user may select a portion of the image by, for example, tapping the subject in a photo to adjust the camera's focus. Based on the depth of that subject on the depth map, an "enhancement region" is created around the subject's depth using a threshold. For example, if the subject is four feet away, the "enhancement region" might include all objects three to five feet from the camera. Finally, the claim describes, "enhancing the enhancement region." This step is the least clear of the five steps, as it is not immediately clear what "enhancing" means in this context. In general, under MPEP 2111, patent applicants may be their own lexicographers. This means that an applicant may offer their own definition for words rather than using the plain and ordinary meaning of those words, provided the words were sufficiently clear in the specification to allow a skilled person to know what they mean. Based on a cursory review of the specification in the '633 patent, enhancing is likely to include at least edge enhancements, adjusting contrast, changing colors, changing geometric shapes, using a high pass filter, and cutting or moving that portion of the image. The exact meaning of claim terms is a very important issue in patent litigation. Therefore, courts will hold a Markham hearing prior to trial, in which both Apple and Qualcomm offer definitions for each disputed term in the patent claims, and the court adopts an appropriate definition. This hearing will determine, for example, exactly what "enhancing" means, as used in the context of claim 1. In October 2016, Apple introduced Portrait Mode. This feature allows iPhone users to take photos with a software-created bokeh, blurring background objects while keeping the subject in focus. This feature is only available on iPhones which have dual cameras, including the iPhone 7 Plus, the iPhone 8 Plus, and the iPhone X. Figure 1: Example of iPhone Portrait Mode Source: MAC World

According to Tech Crunch, "The depth mapping that this feature uses is a byproduct of there being two cameras on the device. It uses technology from LiNx, a company Apple acquired, to create data the image processor can use to craft a 3D terrain map of its surroundings." Some reviews at the time noted that this feature was not an Apple original: Of course, faking bokeh by depth mapping an image and adding in blur is not an original Apple invention by any means, but the Cupertino tech giant seems determined to do it better than it’s been done before. But we’ll let you be the judge of that." - PetaPixel, October 24, 2016 Qualcomm's legal team appears to agree with PetaPixel's assessment. Figure 4: Example Of Portrait Lighting (Stage Light Mono) Source: CNET

Apple has also released Portrait Lighting, for the iPhone 8 Plus and the iPhone X. This feature allows a user to augment existing portraits by using the depth map to adjust the lighting options on the subject and background of a photo. For example, the stage light mono setting discussed at Cnet removes the background and adjusts the subject to be in black and white. Other settings use various other filters on the subject, including softening harsh lighting, adding an even spread of light across a subject's face, and adding shadow contours to a subject's face. Based on a cursory review of the patented claims, Qualcomm's infringement claim appears to be on solid ground. To show infringement, Qualcomm's legal team will need to show infringement of each of the five elements of claim 1. While I do not have access to the algorithms used by Apple's photography software, there is a description found on Tech Crunch. In short, Tech Crunch describes using two images to "separate and ‘slice’ the image into 9 different layers of distance away from the camera’s lens." These layers are then used in various ways in Portrait mode and Portrait Lighting modes, including applying disc blurs to background layers and applying lighting effects to subject layers. The first element of claim 1 ("receiving a left image...") is easily satisfied. Both Portrait and Portrait Lighting mode use two images to create a 9-layer depth map. Similarly, the second element of claim 1 ("determining a depth map...") is also satisfied by the creation of the 9-layer depth map. The third element of claim 1 requires that the subject of an image be "selected by a user." This is also satisfied in Portrait and Portrait Lighting modes. As noted by MacWorld, users can select the subject of a photo: "As with other iPhone photos, you can change the point of focus: tap the object on screen." The fourth element of claim 1 ("determining an enhancement region...") may also be satisfied, although it is more questionable than the first three elements. This element requires that an "enhancement region" be determined, with that region comprising a "continuous portion" of an image, and that has a depth within a threshold of the depth of the subject. Apple may argue here that their subject is not a "continuous portion." Apple may also argue that they are not using thresholds as described in the fourth element. The merits of both arguments will depend on the court's claim construction, which will define the terms used in the patent claims. I expect that the use of 9 discrete layers will count as a "threshold of the first depth," as described in the fourth element. There is little functional difference between selecting a threshold distance compared to establishing nine layers and then selecting a subset of those layers including the subject for enhancement. Further, each of these layers is presumably a "continuous portion," within the meaning of the claim term. This is an element that Apple will contest however, and will likely have at least a colorable claim. Finally, the fifth element includes "enhancing the enhancement region." This element may not be satisfied by Portrait mode, depending how that mode works: If it is simply leaving the layers of the subject as-is, this is unlikely to be "enhancing," while if it sharpens those layers, this would be an enhancement. However, the fifth element is very likely infringed by Portrait Lighting mode, as are the other elements. In Portrait Lighting mode, the lighting on the subject itself can be specifically changed. For example, Cnet describes that "Contour Light" mode allows for "gorgeous shadows to contour the face." As described above, "enhancing" is a bit vague without reference to the specification of the '633 patent. However, with reference to the specification, enhancing appears to include at least edge enhancements, adjusting contrast, changing colors, and changing geometric shapes. Portrait Lighting includes effects that fall into these categories, in my view. Accordingly, I expect that Portrait Lighting mode specifically violates claim 1 of the '633 patent. Apple will have plausible legal claims otherwise, although those legal claims are likely to be resolved by claim construction: The way the court defines disputed terms will be dispositive of whether Apple's various camera modes infringe the '633 patent. In addition to arguing that Apple does not violate the claims of the asserted patents, Apple will also argue that the patents are invalid. This argument will primarily be based on Apple's team of attorneys showing that the inventions within the patents were not new or would have been obvious at the time that those patents were filed. For example, the '633 patent was filed on March 7, 2014. Thus, Apple's attorneys will attempt to find publications and other documents describing inventions that would render Qualcomm's patent obvious to a skilled person at the time that Qualcomm's application was filed. Qualcomm's suit seeks a permanent injunction against Apple plus damages of at least a reasonable royalty for the patents and legal fees. In my view, it is more probable than not that Apple violates the '633 patent. It is also likely that Apple violates some of the other patents asserted by Qualcomm. However, at least some of these patents will also be found invalid (or require narrowing amendments). When a patent is prosecuted before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), the patent examiner does relatively little searching to find prior inventions. He will do a search, and the applicant will submit inventions they believe are related to the patent. The amount of time that the patent examiner and the patent applicant search for prior art is going to be minimal, perhaps a few hours at most. In contrast, patent suit damages can astronomical: One case in December 2016 had a $2.5 billion verdict. Because of the significant stakes, Apple will conduct a far more thorough search for inventions that predate Qualcomm's patents. Apple is likely to turn up inventions, which are stronger, and different than the USPTO's search results, and which are likely to invalidate at least some claims of some Qualcomm patents. Even after that, however, it is likely that Apple will be found to violate some of Qualcomm's patents. But, it is also likely that Qualcomm will be found to violate at least some of Apple's patents, in Apple's patent suits. And both companies know this. Both Apple and Qualcomm have huge patent portfolios, in part as part of a Defensive Patent Playbook. Large corporations such as Apple frequently acquire patents specifically to protect themselves from suits from others, by being able to credibly threaten to counter-sue. Google referenced the defensive value of patents specifically, when it acquired Motorola in 2011: We recently explained how companies including Microsoft and Apple are banding together in anti-competitive patent attacks on Android. The U.S. Department of Justice had to intervene in the results of one recent patent auction to 'protect competition and innovation in the open source software community' and it is currently looking into the results of the Nortel auction. Our acquisition of Motorola will increase competition by strengthening Google’s patent portfolio, which will enable us to better protect Android from anti-competitive threats from Microsoft, Apple and other companies." - Supercharging Android: Google to Acquire Motorola Mobility Similarly, Apple and Qualcomm are aware of this defensive patent strategy. Indeed, this strategy is the reason why Qualcomm responded to Apple's lawsuit with a lawsuit of its own. |

|

|

Contact Us

|

Barry Young

|