Vertical Divider

|

China Continues Smashing Its Internet Companies -- Policy Change or Aberration?

It started when the government effectively canceled the IPO of Ant Financial, then dismantled the company. Jack Ma, the founder of Ant and of e-commerce giant Alibaba, was summoned to a meeting with the government and then disappeared for weeks. The government then levied a multi-billion dollar antitrust fine against Alibaba (which is sometimes compared to Amazon), deleted its popular web browser from app stores, and took a bunch of other actions against it. The value of Ma’s business empire has collapsed. But Ma was only the most prominent target. The government is also going after other fintech companies, including those owned by Didi (China’s Uber) and Tencent (China’s biggest social media company). As Didi prepared to IPO in the U.S., Chinese regulators announced they were reviewing the company on “national security grounds”, and are now levying various penalties against it. The government has also embarked on an “antitrust” push, fining Tencent and Baidu — two other top Chinese internet companies — for various past deals. Leaders of top tech companies (also including ByteDance, the company that owns TikTok) were summoned before regulators and presumably berated. |

|

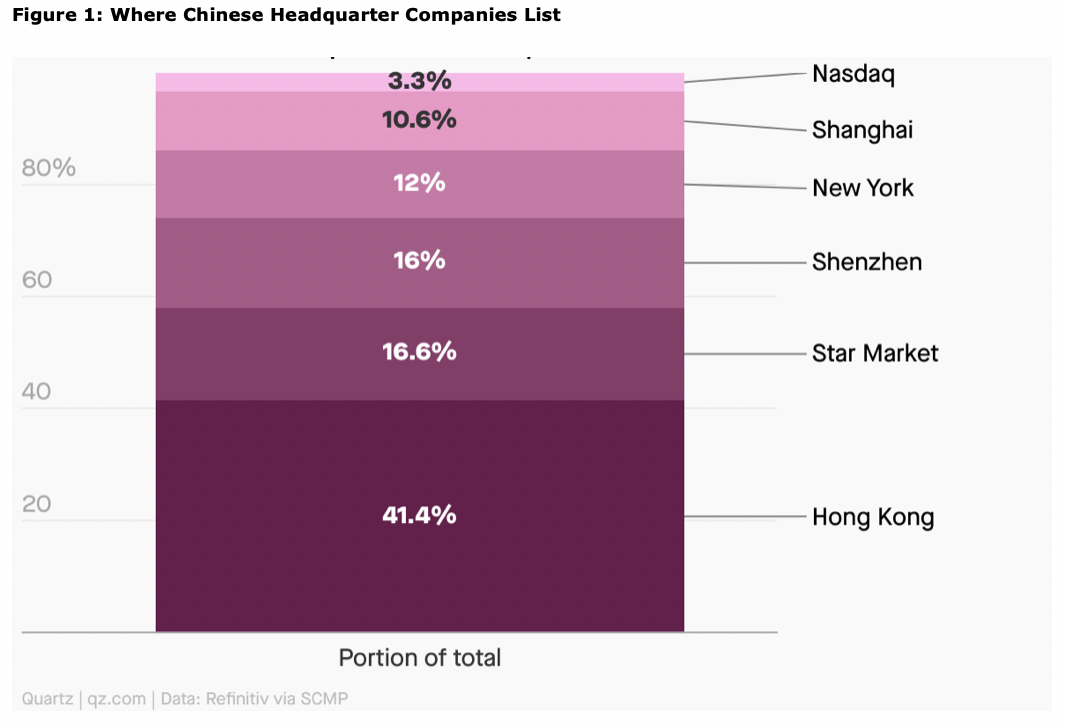

Various Chinese tech companies are now undergoing “rectification”. It’s very difficult to figure out what’s going on. Just who is ordering these actions is not clear, or what the ultimate result of the crackdown will be. That makes it very hard to figure out why it’s happening. Some observers see this as an antitrust campaign, similar to the ones going on in the U.S. or the EU. China’s leaders famously want to prevent the emergence of alternative centers of power, but is the West so different in this regard? One of the driving motivations behind the new antitrust movement in the U.S. is to curb the political power of Big Tech companies specifically; if you wanted to, you might see the Chinese tech crackdown as simply a Neo-Brandeisian movement on steroids. Others see the action as a way to chastise Chinese companies that list their stock outside the home country.

The Chinese government could have decided that the profits of companies like Alibaba and Tencent come more from rents than from actual value added — that they’re simply squatting on unproductive digital land, by exploiting first-mover advantage to capture strong network effects, or that the IP system is biased to favor these companies, or something like that. There are certainly those in America who believe that Facebook and Google produce little of value relative to the profit they rake in; maybe China’s leaders, for reasons that will remain forever opaque to us, have simply reached the same conclusion.

Dan Wang’s 2019 letter, said, “The internet companies in San Francisco and Beijing are highly skilled at business model innovation and leveraging network effects, not necessarily R&D and the creation of new IP….I wish we would drop the notion that China is leading in technology because it has a vibrant consumer internet. A large population of people who play games, buy household goods online, and order food delivery does not make a country a technological or scientific leader…These are fine companies, but in my view, the milestones of our technological civilization ought to be found in scientific and industrial achievements instead.

Are China’s leaders were thinking along the same lines? In his 2020 letter, Dan wrote. “It’s become apparent in the last few months that the Chinese leadership has moved towards the view that hard tech is more valuable than products that take us more deeply into the digital world. Xi declared this year that while digitization is important, “we must recognize the fundamental importance of the real economy… and never deindustrialize.” This expression preceded the passage of securities and antitrust regulations, thus also pummeling finance, which along with tech make up the most glamorous sectors today.

The crackdown on China’s internet industry could be a part of the country’s emerging national industrial policy. Instead of simply letting local governments throw resources at whatever they think will produce rapid growth (the strategy in the 90s and early 00s), China’s top leaders are now trying to direct the country’s industrial mix toward what they think will serve the nation as a whole.

When China’s leaders look at what kind of technologies, they want the country’s engineers and entrepreneurs to be spending their effort on, they probably don’t want them spending that effort on stuff that’s just for fun and convenience. They likely decided that the link between that sector and geopolitical power had simply become too tenuous to keep throwing capital and high-skilled labor at it. And so, in classic CCP fashion, it was time to smash.

Dan Wang’s 2019 letter, said, “The internet companies in San Francisco and Beijing are highly skilled at business model innovation and leveraging network effects, not necessarily R&D and the creation of new IP….I wish we would drop the notion that China is leading in technology because it has a vibrant consumer internet. A large population of people who play games, buy household goods online, and order food delivery does not make a country a technological or scientific leader…These are fine companies, but in my view, the milestones of our technological civilization ought to be found in scientific and industrial achievements instead.

Are China’s leaders were thinking along the same lines? In his 2020 letter, Dan wrote. “It’s become apparent in the last few months that the Chinese leadership has moved towards the view that hard tech is more valuable than products that take us more deeply into the digital world. Xi declared this year that while digitization is important, “we must recognize the fundamental importance of the real economy… and never deindustrialize.” This expression preceded the passage of securities and antitrust regulations, thus also pummeling finance, which along with tech make up the most glamorous sectors today.

The crackdown on China’s internet industry could be a part of the country’s emerging national industrial policy. Instead of simply letting local governments throw resources at whatever they think will produce rapid growth (the strategy in the 90s and early 00s), China’s top leaders are now trying to direct the country’s industrial mix toward what they think will serve the nation as a whole.

When China’s leaders look at what kind of technologies, they want the country’s engineers and entrepreneurs to be spending their effort on, they probably don’t want them spending that effort on stuff that’s just for fun and convenience. They likely decided that the link between that sector and geopolitical power had simply become too tenuous to keep throwing capital and high-skilled labor at it. And so, in classic CCP fashion, it was time to smash.

- This assessment could explain why China would suddenly smash its for-profit education sector.

- Another factor some have suggested (see the comment section) is that the consumer internet companies that China is penalizing have large degrees of foreign ownership.

- One contrary view argues that China’s actions against tech companies are done mainly with the interests of consumers in mind.

- Finally, any assessment of China’s government’s objectives that doesn’t recognize the central importance of comprehensive national power is probably naive. China wants to be a “manufacturing superpower”, but its reasons for doing so that go far beyond providing people with good manufacturing jobs, as shares of China’s semiconductor leader, SMIC, are surging. The immediate impetus for the surge was apparently a rumor of a big order from Huawei, a company that some believe is deeply intertwined with the Chinese military.

- The Chinese government has called video games “spiritual opium”, sending video game stocks plunging. Chalk up another win for my theory.

- Pony Ma, the boss of Tencent, who has utterly sucked up to the Chinese leadership, has lost even more money than the obstreperous Jack Ma in the recent crackdown. This suggests that it’s about the kind of tech the leadership wants, not just about eliminating upstarts who challenge party wisdom.

|

Contact Us

|

Barry Young

|